This is the third in a series of five blog posts that will serve as a guide for practicing “disruptive collection development” in the context of the nonfiction collection. Each day we’ll explore a different category of nonfiction (as developed by Melissa Stewart) along with strategies for thinking critically about the collection development procedures that we employ for selecting, cataloging and shelving those books. The first post in this series unpacks the inspiration for this work. As noted there...

The goal of “disruptive collection development” is to move beyond the occasional infusions of inclusivity offered by intentionally adding, or even focusing on, historically marginalized voices in book ordering throughout the year. While this is surely a best practice, it’s also a strategy that is rendered inconsistent and temporary by its dependence on the whims of staffing and funding. Only through holistic, purpose driven collection development can we move toward more permanent change that is both systemic and procedural.

Thank you to the team at Disrupt Texts who were early readers of these posts and who gave me permission to use the term "disrupt" in this context. Their mission charges us with challenging the traditional canon in order to create more inclusive, representative, and equitable collections. These posts are my attempt to support librarians in using their nonfiction collections as a vehicle for this important work.

To learn more about Melissa Stewart's five categories of nonfiction, I encourage you to visit the first post in this series which contains additional links and context. Links to each remaining post will be added as they are published.

Part 1: Traditional Nonfiction

Part 2: Active Nonfiction

Part 3: Narrative Nonfiction (You are here!)

Part 4: Expository Literature

Part 5: Browsable Nonfiction

Category 3: Narrative Nonfiction

Definition: “Prose that tells a true story or conveys an experience. This style of writing appeals to fiction lovers because it includes real characters and settings; narrative scenes; and, ideally, a narrative arc with rising tension, a climax, and denouement…. Generally features a chronological sequence text structure and is ideally suited for biographies and books that recount historical events..” (Stewart, 2018)

Features:

Narrative writing style

Tells a story or conveys an experience

Real characters, scenes, dialog, narrative arc

Strong voice and rich, engaging language

Chronological sequence structure

Books about people (biographies), events, or processes

Disruptive collection development:

Using Data: The question of “who is the library for?” is one that should guide all of your decision making, including collection development. I often challenge my own students (who are preservice librarians) to consider the following Venn Diagram when crafting new library procedures. While the descriptors for each individual circle may change depending on the unique characteristics of your school's community, a focus on where those circles overlap provides you with an opportunity for disruption.

The kids in the middle of that visual whose access to the library, and its resources, is obstructed by the most barriers, should be the inspiration for most, if not all, of the policies and procedures that guide your work. With that in mind, finding out who these kids are, requires data collection. This data can support your efforts to disrupt traditional collection development practices that tend to privilege capturing the most readers over engaging readers who need the library most. Here are some tips for getting started:

Work with your school’s data manager, social worker and guidance counselor to get a clearer picture of who the kids in the middle of your Venn Diagram are. Once that information becomes available, some questions to inform your next steps include:

do the kids in the center of that diagram see their lived experiences reflected in your selection of narrative nonfiction?

is the narrative nonfiction in your collection accessible and engaging to readers with varied reading identities?

are there specific data points that can guide you towards the kinds of narratives that might serve as touchstones for the readers who need a library and its resources most?

does the narrative nonfiction in your collection contain examples of people and events that disrupt the very systems that most affect your community and, specifically, the kids in the center of your Venn Diagram?

In the catalog: In her essay “Teaching the Radical Catalog,” Emily Drabinksi writes, “Hierarchies centralize power in the ‘first term,’ be it in a dictator in a fascist government, the father in a patriarchal family, or the quarterback in a football team. Less visible is the way that hierarchies privilege only a single aspect of a given object. For example, a man who is a football quarterback may also be a father, a brother, and stamp collector, but for the purpose of the hierarchy that embeds him on the football field, he is only a quarterback. The other relevant parts of his person -his ability to stay in the pocket, scramble, throw the long ball, and so on -are derivative of his "first term," his quarterback-ness. The other parts of his person - his presidency of a local philatelist society, perhaps - become irrelevant. Hope Olson calls this the hierarchy of samenesses." Library classification systems are hierarchies. When librarians add subject headings to local tags, search results are prioritized in response to the hierarchy, with the top terms driving the results with more juice than those that follow. While you may not be able to dismantle and recode your LMS to ignore this hierarchical structure, you can disrupt these systems. Here's some tips for getting started::

Be intentional about the placement of subject headings to prioritize disruption. “Imagine a book about our quarterback that also discussed his struggles with racism in the NFL. A cataloger might assign QUARTERBACKING (FOOTBALL), because it is about football, rather than RACISM-UNITED STATES about racism in America. The book would then be visible to sports researchers, and less so to researchers studying racism in America.” (Drabinski, 2008) Keeping the kids in the middle of your Venn Diagram (above) in mind, disrupt the way narrative nonfiction is catalogued to prioritize search terms that both reflect the readers who most need that book, while also amplifying traditionally marginalized populations. Note: the first post in this series provides more context and information about how to further disrupt subject headings in purchased marc records.

Depending on the age of your readers, this work can serve as the foundation for a powerful discussion. Here's an example of how:

Working with a class that has just completed literature circles featuring some narrative nonfiction, provide each group with a list of the existing subject heading for the titles they've just read. With just a little information about how subject headings influence search results, readers can then debate whether or not the existing heading are sufficient and equitable in both their content and order. As a way to demonstrate learning, then have readers suggest a new list/order for each book they've read. You certainly don't have to use their suggestions, but this activity will provide both you and your readers with some meaningful food for thought, while also giving your community a glimpse into your work as a collection manager.

Selection: One powerful way to disrupt traditional collection development practices is to cede some of the selection power to students, teachers and other community members whose lived experiences can support the work of creating more inclusive and justice oriented collections. Here are suggestions for making this shift:

Create a "friends of the library" committee that includes kids from the center of your Venn Diagram (above).

Personally extend invitations to the kids who need the library most. Involving those readers not only ensures that they feel represented in the library’s holdings, but also empowers them to see the library as a place where they belong and have a voice.

With your guidance, these kids and adults can review potential titles and create lists to inform future purchases.

Because narrative nonfiction can be a bridge that leads kids to reading, it’s essential that titles in this category feature inclusive stories written, edited and illustrated by authors whose lived experience reflect those in the narrative.

Dr. Rudine Sims Bishop described books that “readers have only to walk through in imagination to become part of whatever world has been created or recreated by the author" as sliding glass doors. Narrative nonfiction can serve as a sliding glass door to the very readers who most need examples of defying expectations and disrupting systems, but only if we are intentional in our selection of titles with the power to transform. Prioritize purchases of narrative nonfiction with the most potential to serve as sliding glass doors for the kids in the center of your Venn Diagram.

On the shelf: Here are some tips for disrupting the sea of spine labels that so often define nonfiction shelves:

Weed. Weed. Weed. Remove titles that don't serve as onramps to the outcomes you most want for the kids in the center of your Venn Diagram. Then use the space freed up by that weeding to display books targeting those very readers.

Create a special shelf of narrative nonfiction selected by your "friends of the library" group that mimics the “staff picks” shelves that are popular in bookstores. Add shelf talkers written/recorded by members of that group to highlight their reasons for recommending specific books for the collection.

Using the disrupted search terms/subject headings you prioritized when cataloging new titles, build a display that emphasizes the themes woven across narrative nonfiction that may otherwise seem disparate.

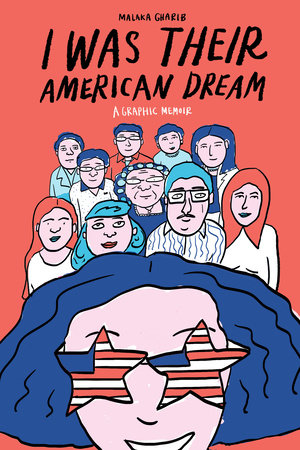

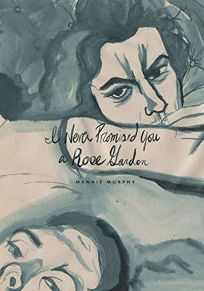

Recommended titles: Some recently published titles that can help you disrupt narrative nonfiction include:

Click on each image for more information about the book.

What's next?

In the days ahead we'll continue examining all of Melissa Stewart's nonfiction categories through the lens of disruptive collection development practices. Tomorrow, we'll take a deep dive into Expository Nonfiction in order to think about how to leverage these focused texts to create more inclusive, representative, and equitable collections.

Acknowledgements:

Thank you again to the founders of Disrupt Texts (Tricia Ebarvia, Lorena German, Dr. Kim Parker, and Julia Torres) for allowing me to partner with them in this work.

Thank you to Becky Calzada, Lynsey Burkins, Franki Sibberson, John Shu and Donalyn Miller for being early readers of this work and for offering your expert feedback.